Optimizing Citrus Production: Practical Guidelines for Effective Foliar Feeding

by Francielle Lima @ University of California Cooperative Extension

Soil fertilization remains the primary method for supplying essential nutrients to plants, as it ensures a steady and sustained nutrient supply through the root system. However, foliar fertilization can serve as a valuable supplement, particularly during critical growth stages when plants have increased nutrient demands or when root uptake is limited due to environmental stress. By applying nutrients directly to the leaves, foliar feeding can provide a quick and targeted boost, enhancing plant health and productivity during these pivotal periods.

Nutrient Requirements and Uptake Dynamics in Orange Trees

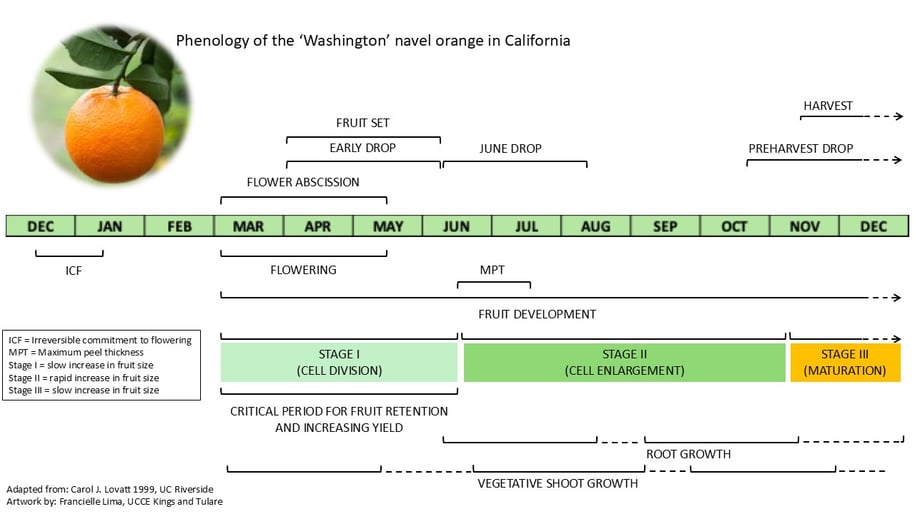

Citrus trees exhibit distinct seasonal patterns in nutrient demand, with the highest requirements occurring during Stage I (flowering and fruit set) and Stage II (fruit development). During Stage III (fruit maturation) the nutrient uptake decreases significantly. Consequently, nutrient availability from March to June is essential for supporting optimal tree development and fruit set.

Stage I is the most critical period for good fruit set and development (Fig. 1). During this stage nutrients must be highly available for physiological processes to occur and generate high yield and fruit quality. Among macronutrients, nitrogen (N) supports vegetative growth, metabolism, and fruit production; phosphorus (P) is involved in photosynthesis, energy metabolism, and nutrient translocation; potassium (K) contributes to fruit formation and quality; calcium (Ca) is essential for cell division, elongation, cell wall integrity, membrane stability, and root development; and magnesium (Mg) plays a central role in photosynthesis and enzyme activation. Micronutrients such as manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), and zinc (Zn) are essential for enzymatic functions, photosynthesis, and N metabolism.

Fig 1. Phenological model of navel orange, based on mature ‘Washington’ navel cultivar grafted onto ‘Troyer’ citrange rootstock.

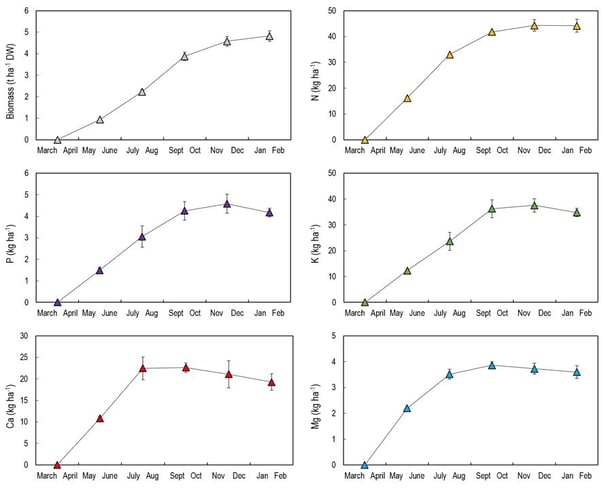

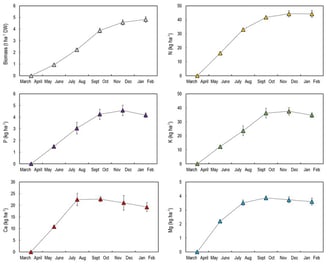

In a three-year study (2017–2019) on mature orange trees in California’s Central Valley, the accumulation patterns of N, P, K, Ca, and Mg in fruit showed rapid uptake during the early season, with approximately 90% of N, P, and K and 80% of Ca and Mg accumulated by late September-early October. Generally, the concentrations of N, P, and K were high at the beginning of the season and remained relatively stable until harvest. In contrast, Ca and Mg concentrations were also high early in the season but declined progressively until fruit harvest (Fig. 2). Overall, macronutrient uptake primarily occurs between March and late August, with minimal net absorption after October.

Fig. 2. Seasonal trends in fruit biomass and macronutrient accumulation in mature orange trees in California’s Central Valley. Bars represent standard errors. (Courtesy: Patrick Brown and Douglas Amaral).

When to Spray: Getting the Most from Foliar Fertilizers

Nutrient management must be carefully planned based on soil, tissue, and water analyses, which help diagnose the actual needs of the trees, as well as on the orchard’s historical, including past fertilization practices, yield levels, and any nutrient deficiencies. Furthermore, cultivated varieties may have high nutrient demands, which highlights the importance of specific nutrient management.

For example, pre-bloom foliar applications, carried out in early spring before full flowering, are particularly effective because they support the initiation of flowering, the development of reproductive organs, and the early stages of leaf and shoot expansion. Nitrogen foliar application during this stage is especially beneficial when soil conditions are cold or wet, limiting root N uptake and N foliar provides a rapid and available form under such conditions. Phosphorus foliar sprays are most effective when applied pre-bloom, improving fruit set and overall yield. Micronutrient foliar sprays are most effective when applied during the spring flush, targeting leaves that are nearly fully expanded but still physiologically active. Thus, the pre-bloom period is also optimal for correcting micronutrient deficiencies, particularly Zn and Mn.

Post-bloom foliar applications are performed immediately after petals fall and may extend through June. During this period, citrus trees experience rapid cell division and active fruit development. The demand for N remains high, driven by simultaneous fruit set and vegetative growth. Potassium applications are valuable in maintaining growth momentum and improving fruit quality parameters, including size and peel thickness.

Summer foliar sprays may be adapted to meet specific production goals. To increase fruit size, avoid using either fertilizer as a winter pre-bloom spray, and apply N or K only in summer. For earlier harvests or to increase peel thickness, K and P (potassium phosphite) should be applied in May and July.

Potassium phosphite may also contribute to the control of Phytophthora spp. and help mitigate the effects of HLB. In Valencia oranges close to harvest, prefer potassium phosphite to avoid regreening. Use it also when crease is an issue, either as a pre-bloom or summer maximum peel thickness (MPT) spray.

Choosing the Right Fertilizer for Foliar Sprays

Mature and fully expanded citrus leaves are capable of efficiently absorbing several nutrients through foliar applications. These nutrients include N when supplied as urea, along with K, Mg, Ca, S, Zn, Mn, and B, provided as soluble salts or chelated compounds. Nitrogen is commonly applied using low-biuret urea, which contains less than 0.25% biuret, making it suitable for sensitive crops such as citrus. Furthermore, urea-N uptake is greater than nitrate-N or ammonium-N uptake for citrus leaves. Potassium nitrate also serves as an effective N source through foliar feeding, while simultaneously contributing K. Additional K-containing fertilizers, including potassium phosphite, potassium thiosulfate, monopotassium phosphate, and dipotassium phosphate, are used to correct specific nutrient deficiencies.

Foliar applications of low-biuret urea (46-0-0, < 0.25% biuret; 50 lbs per acre in 200 gallons of water) or potassium phosphite (0-28-26; 0.64 gal per acre) winter pre-bloom, particularly between December 15 and February 15, have been associated with increased fruit yield, total soluble solids, and support heavy on-crop. These applications stimulate flower initiation and retention, but late treatments (March-April) mainly enhance the retention of reproductive structures rather than initiate new floral meristems. Earlier or excessively late applications (October-November or after June drop) are less effective due to flower and fruit abscission processes that reduce yield potential.

Summer foliar applications aim to increase fruit size rather than yield by extending the cell division phase, which concludes around late July, marked by MPT. For this purpose, low-biuret urea (46-0-0, < 0.25% biuret; 50 lbs per acre in 200 gallons of water) is applied around July 15 (± 7 days), while potassium phosphite is most effective when applied in two applications on May 15 ± 7 days and July 15 ± 7 days (0.5 gal per acre twice). Summer applications before MPT (e.g., in May or early June) may increase fruit retention but are less effective in enhancing fruit size.

Potassium nitrate (30 lbs per acre in 100 gal of water) can be applied to correct K deficiency, and the best time for foliar application is when leaves of the first spring growth flush are expanding (March-April). One spray is sufficient for a mild deficiency.

Early morning is the ideal time for foliar application, as stomata are open, and the tree is actively taking in water and nutrients. Temperature and humidity affect absorption, so avoid spraying when temperatures exceed 80°F. In winter, midday applications are best when temperatures are warmer. Foliar nutrients should be applied in highly soluble forms, with a solution pH between 5.5 and 6.5. This is particularly important in areas where water quality is poor. The fertilizers should be diluted enough to ensure full canopy coverage with fine droplets. It is also important to avoid runoff and over-misting to prevent tip burn and drift.

Response of HLB-Infected Citrus Trees to Foliar Nutrient Applications

Nutrient uptake efficiency in HLB-affected citrus trees tends to be at the lower, largely due to root loss, which can reach up to 80% depending on disease severity. Thus, the HLB infection reduces severely water and nutrient uptake. There is currently no proven strategy to prevent HLB-induced root loss. However, root density in affected trees may be improved through adjustments in irrigation and fertilization practices that better balance water and nutrient supply.

Micronutrients such as Zn and Mn are commonly deficient in HLB-affected trees, and foliar applications are particularly useful in supplying these nutrients. An integrated approach that combines efficient fertigation with targeted foliar applications represents a promising strategy to mitigate the adverse effects of HLB, support root health, and sustain citrus productivity. In HLB-affected trees, foliar fertilization should be regarded as a supplement to, rather than a replacement for, soil-based nutrient management.

In citrus production, the success of foliar fertilization depends on thoughtful integration into an overall nutrient management strategy. By tailoring foliar applications to orchard-specific needs and aligning them with crop development stages, growers can optimize tree health, improve fruit quality, and support resilience under challenging conditions such as HLB. Continued field observations and collaboration with crop advisors will ensure that foliar nutrition remains a precise and valuable component of citrus fertility programs.

Disclaimer:

The information presented in this article is intended for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as a specific fertilizer recommendation. Nutrient management should be tailored to the unique conditions of each orchard, including soil characteristics, tree age, variety, and local environmental factors. Growers are encouraged to work with qualified agricultural advisors or conduct site-specific testing to develop an effective and balanced nutrient management plan.

Useful Links:

CDFA/UC Davis - California Fertilization Guidelines: Citrus

A Guide to Citrus Nutritional Deficiency and Toxicity Identification

A New Approach to Best Nitrogen Management Practices in Citrus